Who We Are

OUR REVIEW PROCESS

We, the scientists and clinicians who created MyMenoPlan, have carefully evaluated the scientific literature to develop our recommendations.

- Each page is reviewed by several scientists actively working on menopause research. You can see our names at the bottom of the pages.

- You can see our sources, too. References are at the bottom of the pages.

- Here are links to all of our studies about menopause.

- We are unbiased. Our funding comes from US tax dollars through the National Institutes of Health, not from private companies like drug or supplement manufacturers. We are not trying to sell you anything.

HOW CERTAIN ARE WE? GRADING THE EVIDENCE

We give the evidence in each area a grade, based on how certain we are that it helps, in ineffective, or hurts people. You’ll see the following in your Menoplan, and on the symptom and treatment pages.

- Helps – the evidence is compelling that the treatment or coping strategy helps women on average. Typically, there are good quality studies and systematic reviews of the all the research in an area. One more study wouldn’t make a difference. (See more on how we judge quality below.)

- May help – there are at least some studies that show a good effect, but more research is needed to be sure. There might be too few studies. The research may have flaws. Bottom line: we are not certain that the treatment helps for the symptom on average.

- Does not help – research has found that the treatment does not work well for that symptom.

- May hurt – ooops! Research found that not only did it not work, but it had some bad effects.

- Not studied – there’s reason to think that the treatment might be helpful, but we don’t know. The research base is insufficient. Existing research might be low quality or conflicting. We need more research.

- Not relevant – logically, the treatment could not help that symptom. It seems to be biologically irrelevant, with what we know today.

BASING OUR ADVICE ON THE BEST SCIENCE

The MyMenoPlan research team is committed to giving you the best available advice based on the highest quality research. What does that really mean?

- The treatment has to help.

Tests of a treatment should show a bigger effect in women who were given the treatment than in women were given a placebo (discussed more below).

- The difference needs to make a difference to the women.

Scientists use statistics to judge whether a treatment really works. But sometimes statistically significant effects are so small that a woman wouldn’t really notice. The degree of impact should matter to the sufferer. Doctors talk about whether the impact is clinically meaningful. You should feel at least a little better from the treatment.

- The research quality is high enough to convince us the conclusions are right.

We looked at all the research about the treatments. No cherry picking which studies to pay attention to because we’re rooting for a treatment we personally like. This is why you should not jump when the news reports one new study. It’s only that – one new study. It needs to be considered along with all the other studies in an area.

One way we judge the research quality is using techniques that combine the findings of many studies. This is called a meta-analysis or systematic review. For many of the treatments we write about, there have been meta-analyses telling us whether the treatment works, for whom, and how strong the effect is on average. If averaging the results of all the studies finds that a treatment improves a symptom, then it is a more likely to be true.

We consider how many studies there are, how big they are, whether they were randomized trials, how they chose the participants, and how they measure the results. There should be enough studies to know whether results are reliable – meaning the studies get similar results. One study is not enough to know whether a treatment works.

- There have been randomized trials of the treatment. Randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard in research, because it’s the best way to figure out causality. Did the treatment really help the symptom? Read more about randomized controlled trials, and the placebo effect below.

WHAT IS A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL?

There are many types of studies. Some studies are observational. That means that we compare groups based on certain traits –young people vs. older people, people who drink well water vs those who drink city water, or women with a natural menopause vs. those with a surgical menopause.

Imagine we compare the rates of disease in these groups. It may be, for example that people who drink well water are more likely to get a certain disease than those who drink city water. But there can be bias in this kind of comparison. Maybe people who drink well water are also more likely to be exposed to pesticides and it is really the pesticides that cause the disease. It is hard to account for these types of biases in observational studies.

That is why the gold standard is a randomized controlled trial. In randomized trials we take people who are eligible and want to be in the study. Then they are randomly assigned (like tossing a coin) to two or more groups. One group gets the treatment we are testing. The other group is a control group, and it gets a matching placebo treatment. We try to make the groups alike except for the treatment they get. Then we can be more confident that the treatment caused a change in the symptom. Examples of study treatments and their matching placebos or control treatments are shown below.

| Study Intervention | Placebo/Control Intervention |

| Antidepressant Pill | Sugar Pill |

| Vaginal Cream with Estrogen | Vaginal Cream without estrogen |

| Yoga for Menopause | Education Group for Menopause |

| Real acupuncture | Sham Acupuncture |

Is this necessary? After all, it would be easier and less expensive to compare hot flashes in women who do and don’t take antidepressants. But what if more women with hot flashes just happen to also use antidepressants? Then it could look like antidepressants cause hot flashes (which is not true).

That’s why, in a randomized controlled trial women are randomly assigned to use the antidepressants or not. We start with women who have hot flashes and are not on antidepressants. Half are assigned to take antidepressants, and half get a placebo. Then we can see if the women assigned to take antidepressants have fewer hot flashes than the women who not given antidepressants. With this design, we are more sure of causality. (Which, it turns out, is true. Antidepressants cause women to have fewer hot flashes.)

Do we have to use a placebo, like a sugar pill? Why can’t we just give antidepressants to women with frequent hot flashes and see what happens to their hot flashes? The problem with this is the placebo effect.

WHAT IS THE PLACEBO EFFECT?

A placebo is an inactive agent (like a sugar pill) or a sham procedure (like a fake vaccine). It is used in a randomize controlled trial to play opposite the real intervention. Some people get the real intervention, other people get something they think is real, but isn’t.

Why is this important? Because placebos can cause real physiological changes in the brain that influence health outcomes, such as hot flashes or pain. Expectation plays a huge role in the perceived and physical response to a treatment. A person who thinks they are getting the real intervention but is given a placebo still experiences the ritual and attention involved in the intervention. The design – intervention vs placebo – means that people in both groups should have similar expectations, desires, anxiety, perceived rewards, mental cues, and emotions.

This way scientists can separate the effects of the specific intervention from the effects of any intervention. The effects of the specific intervention are those above and beyond the effects of the placebo group.

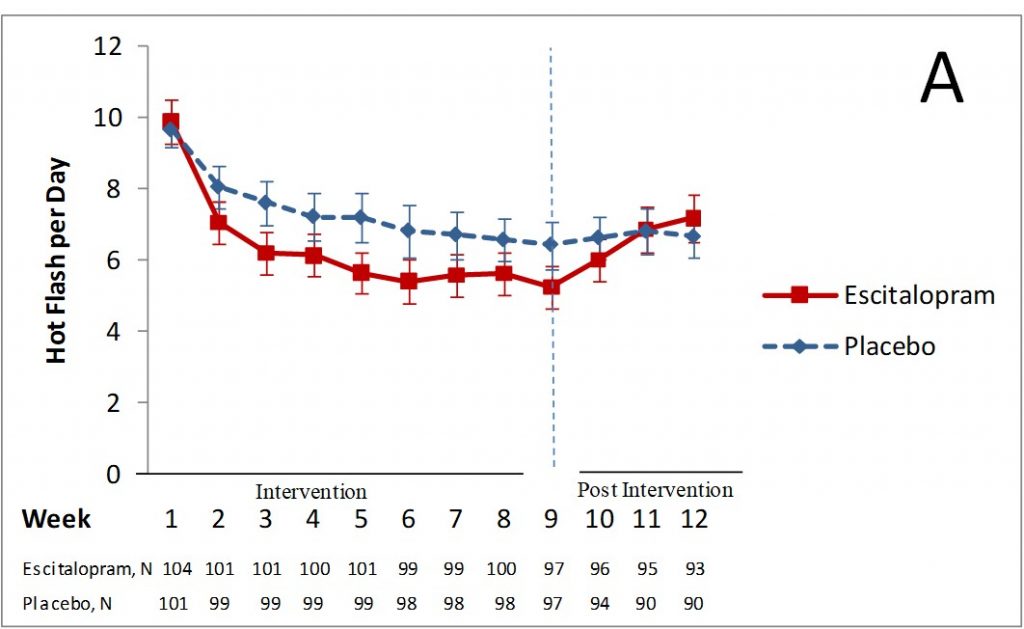

For example, in studies of hot flashes, women in the placebo group usually report a 30-50 percent decrease in hot flashes. We found this is our own studies. We did a study looking at the effect of the antidepressant, escitalopram, on hot flashes. At the beginning, women in both groups had about 10 hot flashes per day. The graph below shows the lines starting at the same point. After 8 weeks, on average, women taking the placebo (the dashed blue line) had about 7 hot flashes per day – a 33% decrease in their hot flashes. Women taking escitalopram (the solid red line) had about 5 hot flashes per day – a 46% decrease in their hot flashes. Three weeks after the intervention, when both groups stopped taking their drugs, the number of hot flashes were the same again.

Without the placebo comparison, we would think the effect of the drug was greater than it was. The real effect of the drug was the difference between the two lines. Just being in the study was beneficial, too – the placebo effect.

Because of strong placebo effects like the study above, we think that randomized trials of menopause treatments are critical.

REFERENCES

Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari M, McDonagh M, Balk E, Whitlock E, Reston J, Bass E, Butler M, Gartlehner G, Hartling L, Kane R, McPheeters M, Morgan L, Morton SC, Viswanathan M, Sista P, Chang S. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC130-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2013.

Brody H. Meaning and an Overview of the Placebo Effect. Perspect Biol Med. 2018;61(3):353-360. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2018.0048. PMID: 30293974.

Girach A, Aamir A, Zis P. The neurobiology under the placebo effect. Drugs Today (Barc). 2019 Jul;55(7):469-476. doi: 10.1358/dot.2019.55.7.3010575. PMID: 31347615.

Hashmi JA. Placebo Effect: Theory, Mechanisms and Teleological Roots. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2018;139:233-253. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2018.07.017. Epub 2018 Aug 6. PMID: 30146049.

Weinberger JM, Houman J, Caron AT, Patel DN, Baskin AS, Ackerman AL, Eilber KS, Anger JT. Female Sexual Dysfunction and the Placebo Effect: A Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;132(2):453-458. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002733. PMID: 29995725.

Authors: Dr. Katherine Newton & Dr. Leslie Snyder. Last updated on April 25, 2021.